Photograhies : FLORIAN TOUZET

Emmanuelle Roule is a designer and ceramist. She first dug her hands into clay in 2012. In 2019, she established Patrimoine Vivant - Living Heritage - an applied research project focused on earthen materials and their possibilities, questioning our production methods and the way we construct spaces, furniture and other objects in an economic, disrupted and changing ecological context. In particular, she develops clay/biopolymer combinations such as natural beeswax and vegetable fibres.

A project that links design, architecture, crafts and lifestyle. A meeting with a researcher who is passionate about earthen materials.

Do you have a particular ritual to tune you into your creative process in the studio?

When I enter the workshop. I look at the pieces in progress, often in the drying phase; then I take out my loudspeaker, I start the music, I put on my workshop clothes, adequate shoes and I slip on my work apron. Then I select the tools I need for the session and get started.

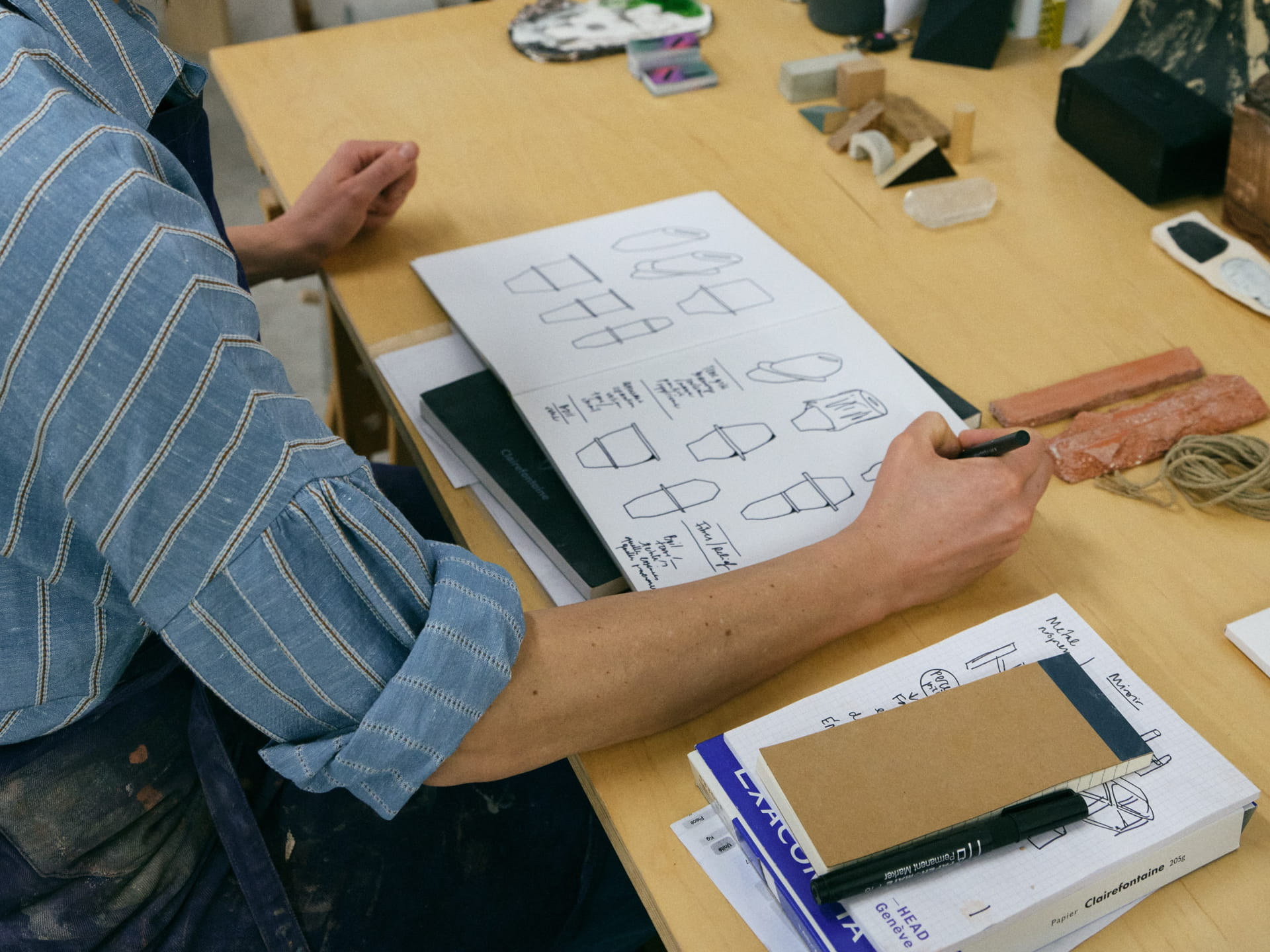

Can you tell us about the piece you created for Sessùn's "Floraison Créative" carte blanche?

I have created a series of new pieces, halfway between design and art. A series of 5 wall lights, which are unique sculptural pieces with forms inspired by architecture and anthropomorphism. This series named SUMU refers to others, to diversity, to cohabitation and to an idea, a way of inhabiting space. All the pieces are made of white stoneware, raw or glazed, fired at low or high temperature, with shades of beige and matte, textured finishes, highlighted by the light source that passes through them.